Best Management Practices for Weed Control in Winter Wheat

November 6, 2024

- Management practices that improve the competitiveness of wheat stands can aid in weed control efforts.

- Fall burndown applications may be the best time to control some grassy weeds in winter wheat.

- Weed spectrum, crop rotation, and type of wheat, can affect weed management strategies.

- Volunteer wheat should be controlled before planting another wheat crop.

- The critical period of weed control in wheat is generally considered to be from early emergence through the boot stage, or between approximately 600 and 1400 growing degree days for winter wheat.1,2

A wheat crop that is weed free during stand establishment (Figure 1) is important for wheat quality and yield. It has been estimated that winter and summer annual broadleaf weeds can reduce yield in winter wheat by about 10%.3 The quality of harvested grain and harvest efficiency is also affected by weed growth. Some weeds can produce large amounts of green vegetation (Figure 2) that hinder harvest equipment, increase moisture and foreign matter, and potentially lead to dockage at the grain terminal. Volunteer wheat can also harbor insects between wheat crops and promote diseases.

Cultural Control Practices

Weed heights can be kept short and herbicides more effective if cultural practices are used to make wheat more competitive with weeds. Crop height, later planting dates and early cultivation can help control some weed species.

- Winter wheat products that are standard height are more competitive compared to semi-dwarf wheat.

- Cultivation can be used to force germination in some weed species such as wild oat, which typically is dormant and has delayed emergence. Once emerged, weeds can be controlled with tillage or herbicides.4

- Later planting dates allow for early-emerged weeds to be controlled with a burndown application or tillage prior to crop planting.

Scouting for Weeds

Several critical periods during which scouting can help to determine the presence and density of weeds in winter wheat include:

Early October. Look for cool season weed species, especially in no-till fields.

Mid- to late November. Some weeds that begin growth in early fall may potentially grow too large to effectively control in the spring. Examples of cool season annuals include Italian ryegrass, common chickweed and henbit.

Early March to early April. Monitor weed presence after the wheat breaks dormancy but prior to the Feekes 6 growth stage (jointing). Some herbicides require application prior to jointing so be sure to identify the growth stage of the wheat and consult the product’s label.

Late May to early June. After the wheat has headed, look for warm season weeds that may be emerging and could potentially cause problems for harvesting equipment, as well as producing seed that could be spread during harvest operations. Preharvest applications should be delayed until after the wheat kernels have reached the hard dough stage.5

Fall Burndown

The focus of burndown applications prior to seeding wheat is to control small, emerged weeds that could reduce yield potential and for which in-crop control options may be limited, less effective, or more costly.6 Downy brome and Japanese brome are grass species that are better controlled with early fall, late spring, or mid-season applications. Brome species can be controlled with higher rates of propoxycarbazone in-crop.

In-Season

Identifying growth stages of wheat is important for proper timing of herbicides applications. Crop injury may not always cause yield loss, but weeds allowed to compete with the wheat have been reported as causing over a 10 percent yield loss.7 Some synthetic auxin herbicides (also called growth regulators, herbicide group 4), if applied after jointing, can cause malformed heads or twisted flag leaves because of rapid stem extension. Herbicides applied outside of the recommended growth stages may result in kernel abortion and blank wheat heads. Many in-season grass herbicides include a safener for wheat. Safeners protect crops from herbicide injury by increasing the activity of detoxification enzymes. The label for these products may provide very specific recommendations for crop and weed stages. Other herbicides may have pre-harvest intervals or restrictions on using harvested seed or hay. Whether applying pre- or post-emergent products, farmers should check local recommendations or with their agronomist.

Crop Rotations Involving Wheat

Continuous wheat. Grassy weeds such as wild oat can build up in these rotations. Certain active ingredients such as sulfosulfuron may be an option in continuous wheat since the long residual activity of this herbicide may restrict planting options for the following rotational crop. This can range from 12 to 22 months, depending on geographic location, for planting to corn, sorghum, cotton, sunflower or soybean following wheat.8

Wheat-soybean double crop. In regions where the growing season is long enough, there may be time to plant a soybean crop immediately following wheat harvest (Figure 3). Controlling weeds in wheat stubble will have two priorities: 1) controlling already emerged weeds and 2) preventing later flushes of weeds. In many cases, the emergence of most summer annual weeds has taken place. However, some species, such as waterhemp and Palmer amaranth, can continue to establish new seedlings during mid- to late summer, although usually at lower densities. Soybean planted into wheat stubble will likely have rapid emergence, typically in about four days, due to warm soil temperatures, and can establish the canopy quickly. The critical time for controlling weeds is shorter in this rotation. Burndown applications can be made as soon as harvest is completed. Adding a residual herbicide may allow for a one-pass weed control program, assuming there is adequate moisture for activation. Keep in mind which crop will follow the next spring when selecting a residual product since some herbicides may have up to 10-month restriction for planting to corn or other crops.

Soybean-wheat. One consideration for planting winter wheat following soybean harvest is that some herbicides used in soybean may have plant-back restrictions for wheat. The goal should be to establish a vigorously growing stand of wheat prior to winter dormancy. However, planting date for winter wheat is dictated by soybean harvest. Time can be short for the spray operation and winter annual weed species may germinate during this time. Tillage may not be practical with scarce moisture or approaching frost but seeding rate and wheat product selection can be adjusted to achieve a dense, healthy stand. Earlier seeding dates, with early soybean harvest, means winter wheat can reach canopy formation and seeding rate can perhaps be reduced.

Wheat-fallow-wheat. Large summer annual weeds in fallow acres may need to be controlled to avoid interference with planting equipment and improve seedbed conditions. A fallow period can be used to control a problem weed such as downy brome. Tillage immediately after harvest would stimulate weed seed germination. Downy brome seedlings could either be tilled again or controlled with herbicides.

Clearfield® wheat followed by corn or other row crops. Herbicide tolerant spring and winter wheat products are available as Clearfield® or Clearfield® Plus brand products in some regions. In this cropping system, the continuous use of herbicide products containing imazamox could increase selection pressure, and the potential for a weed species to develop resistance. Product stewardship is in place with specific technology rotation restrictions agreed to by the grower in the BASF Clearfield® Licensing Agreement. Herbicides with a site of action other than ALS inhibitors (herbicide group 2) should be considered for the third crop in a Clearfield® wheat rotation. For example, corn could use a soil-applied option such as a seedling shoot growth inhibitor containing acetochlor or metolachlor (herbicide group 15) along with a post-applied photosynthesis inhibitor such as atrazine (herbicide group 5) or EPSP synthase inhibitor (glyphosate, herbicide group 9).

Harvest and Post-Harvest

Glyphosate can be applied pre-harvest to wheat once it has reached Feekes 11.3 growth stage which is physiological maturity, or the hard-dough stage (maximum kernel dry weight). Harvest efficiency and grain quality can be improved by the suppression or control of large, troublesome weeds. Late-season weed flushes may interfere with harvester operations or result in potential dockage at the elevator. A seven-day pre-harvest interval is required after the applications. Do not apply glyphosate to wheat that is grown for seed.

Season-long control often reduces weed populations and vigor after harvest. Post-harvest weed control should be timed to limit moisture loss to weeds and prevent the deposit of more weed seeds in the soil. Weeds that have been cut at harvest should have active regrowth occurring before applying herbicide.9

Volunteer wheat that emerges after harvest can serve as a “green bridge” to the next wheat crop by hosting insect pests such as the wheat curl mite and Hessian fly along with numerous wheat diseases. If volunteer wheat has emerged, it should be killed at least two weeks before seeding a new crop of wheat.10 This is to allow enough time for insects to leave the area or die before the next wheat crop emerges.

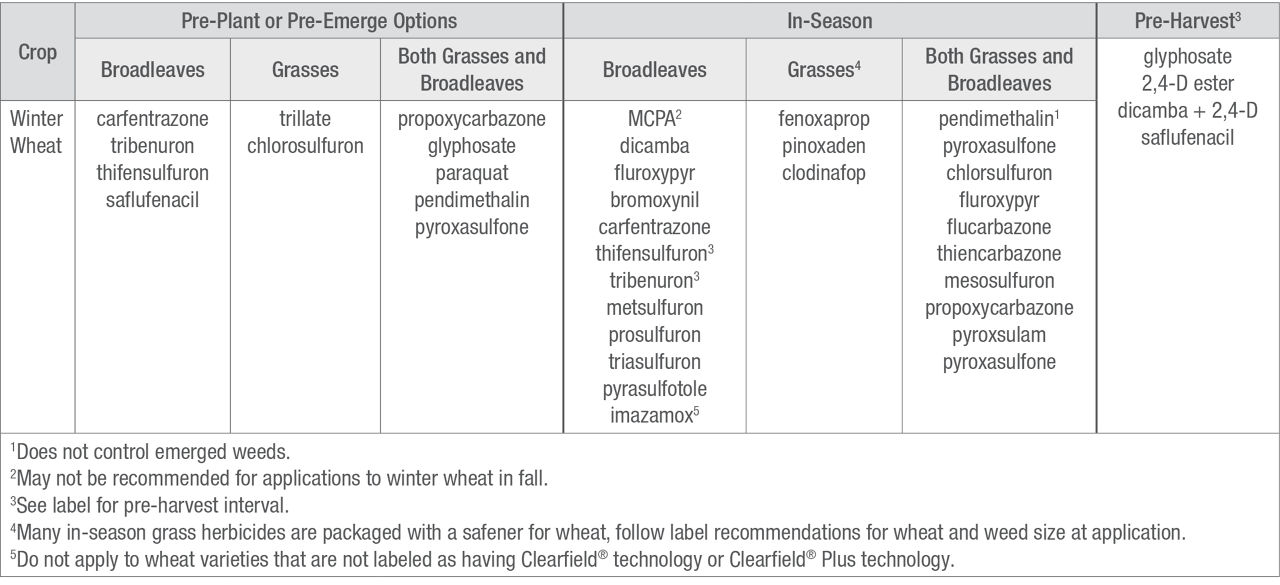

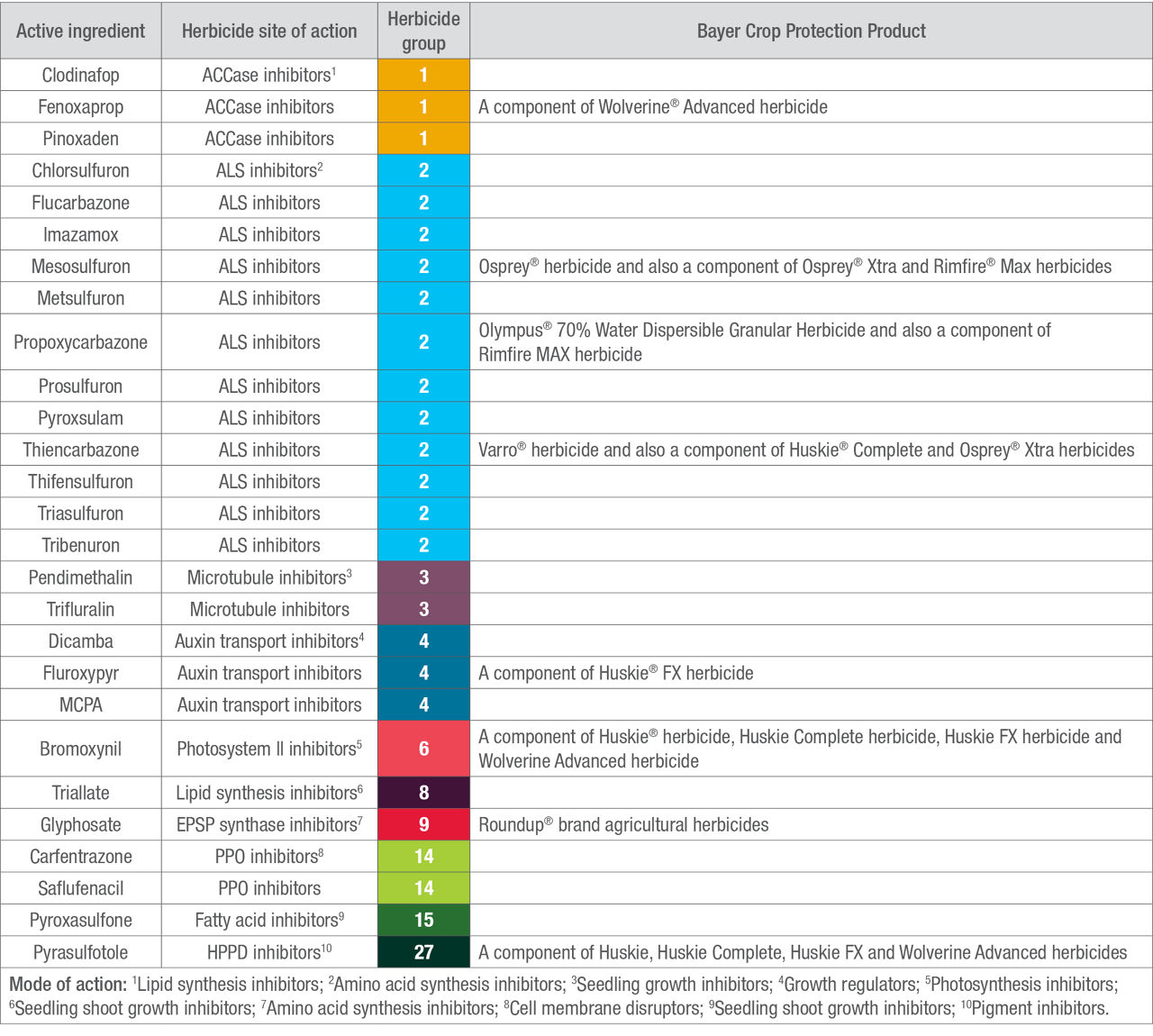

Table 1 lists herbicide active ingredients that are labeled for use in winter wheat, the type of weed that is controlled by the active ingredients, and the timing of application. Table 2 lists the active ingredients sorted by their site of action and herbicide group number.

Table 1. Herbicide active ingredients options for PRE and POST timing in winter wheat.

Table 2. Herbicide active ingredients categorized by site of action and herbicide group.

Sources:

1Redmond, C., Knapp, M., and DeWolf, E. 2021. New Kansas Mesonet tool for estimating wheat growth stage. Agronomy eUpdates. Kansas State University Extension. https://eupdate.agronomy.ksu.edu/eu_article_prep.php?article_id=2784

2Miller, P., Lanier, W. and Brandt, S. 2001. Using growing degree days to predict plant stages. Montana State University Extension Service. https://landresources.montana.edu/soilfertility/documents/PDF/pub/GDDPlantStagesMT200103AG.pdf

3Klein, R. N., Lyon, D.J. and Young, S. L. 2012. Annual broadleaf weed control in winter wheat. University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. NebGuide G1241. https://extensionpubs.unl.edu/publication/g1241/2012/pdf/view/g1241-2012.pdf#:~:text=They%20compete%20for%20water%2C%20light,estimated%2010%20percent%20each%20year.

4Martin, J. R. and Green, J. D. 2009. Weed management. Section 6. A comprehensive guide to wheat management in Kentucky. ID-125. University of Kentucky. https://publications.ca.uky.edu/sites/publications.ca.uky.edu/files/ID125.pdf

5Ikley, J., Christoffers, M., Dalley, C., et al. 2024. 2024 North Dakota Weed Control Guide. W253-24. North Dakota State University Extension. https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/weeds/weed-control-guides/2024-ndsu-weed-guide-2/2024-ndsu-weed-guide

6Burndown herbicides for no-tillage wheat. C.O.R.N. Newsletter 2014-32. The Ohio State University. https://agcrops.osu.edu/newsletter/corn-newsletter/2014-32/burndown-herbicides-no-tillage-wheat

7Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Publication 811. Chapter 13. Weed Control

8Avalaire Sulfosulfuron™ label. 2021. EPA registration No. 93930-79. United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://www3.epa.gov/pesticides/chem_search/ppls/093930-00079-20211209.pdf

9Klein, R. 2014. Controlling weeds post-harvest in winter wheat. CropWatch. University of Nebraska Extension – Lincoln. https://cropwatch.unl.edu/controlling-weeds-post-harvest-winter-wheat

10Shroyer, J. 2011. Volunteer wheat control can help protect yields. Kansas State University. Plant Management Network.

Web sites verified 09-09-2024. 1823_174148

You may also like...

Here are some articles that may also be of interest to you