What You Need to Know About Cotton Shed

August 12, 2024

- It is important to figure out why a cotton crop is shedding bolls instead of setting bolls to manage the crop in a way that promotes flowering and boll production.

- Cotton relies heavily on the supply of carbohydrates produced during photosynthesis for boll setting. When carbohydrate demand exceeds supply, cotton will respond by shedding the youngest fruit (young squares and bolls) to maintain larger, older bolls.1

Q. Why are there so many squares and bolls lying on the ground?

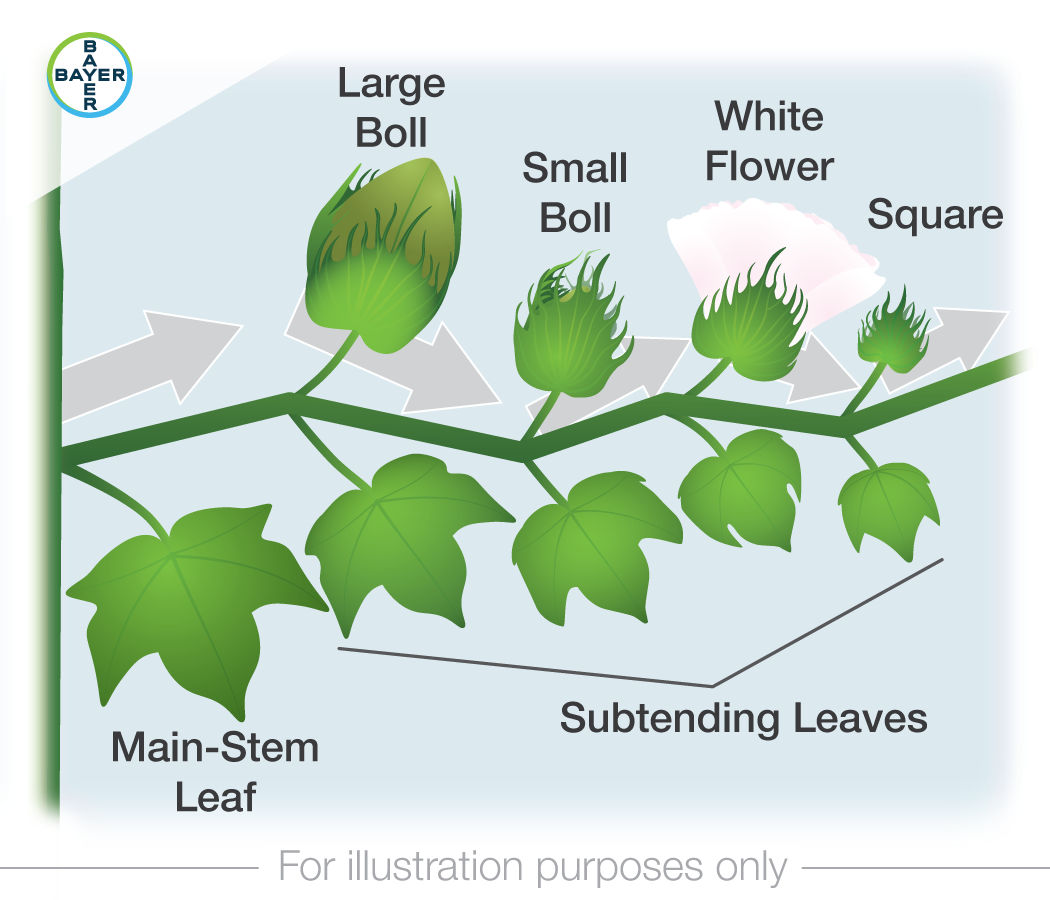

Cotton boll retention is influenced by a complex interaction of hormones, nutrients, and environmental conditions. Plant growth and development can be limited by insect feeding, diseases, water stress, or excessive heat, any or all of which can reduce the supply of carbohydrates available to the plant. While some amount of shedding can be expected throughout the season, managing stress to the cotton crop can help improve boll retention and preserve yield potential. Stressed plants adapt to limited resources by shedding squares (Figure 1) and young bolls to retain larger fruit on the plant.2 The following are some of the stressors that may cause cotton plants to shed. Note that the squares and bolls may not be shed until several days after the stress has occurred.3

Soil moisture. If adequate soil water is not available to the plant, squares and small bolls may be shed until moisture conditions improve. Saturated soil can also lead to boll shed if nutrients have leached through the soil profile, or if limited oxygen is available to the roots.2

Poor light penetration through the canopy. Cotton plants rely heavily on the supply of carbohydrates from subtending leaves which are the leaves that are located closest to each boll (Figure 3). Bolls that are set lower on the plant need light to penetrate through the canopy to the subtending leaves for carbohydrate production.1 Rank growth, excessive plant population, or cloudy weather are several factors that may reduce light penetration and potentially result in square and boll shed. If cloudy weather arrives with rain, pollination may be reduced, and poorly pollinated flowers may also be shed.2

Very high temperatures. Cotton is a tropical plant and tolerates heat well, but extreme heat (>90 °F) can lead to plants using carbohydrates quickly to keep cool. Increased carbohydrate use is especially a problem when nighttime temperatures remain high, because the plants must constantly respire to keep cool. In this situation, young bolls and squares will shed so the plant can maintain the larger set bolls.2

Insects and diseases. Boll shedding due to insect injury and diseases can be direct or indirect. Direct feeding by insects on squares or bolls can provide an entry point for pathogens such as fungi and bacteria, which can cause boll rots that potentially result in shedding. Cotton fleahopper, Lygus spp. (e.g., tarnished plant bug), cotton bollworm, pink bollworm, and tobacco budworm are known to feed on squares and bolls.2 Indirect damage to cotton bolls can occur if feeding reduces the leaf area (e.g., through leaf feeding by insects or lesions caused by foliar diseases) or damages the plant’s vascular system.2,3

Nutrient availability. Nutrient deficiencies can lead to the shedding of young bolls and reduce boll retention; therefore, a complete, carefully planned nutrient package—including calcium, boron, and zinc—is needed to reach optimal growth and development.2 An overapplication of nitrogen (N) can lead to rank growth, potentially limiting light penetration into the lower canopy. However, N is more commonly a limiting factor for growth. Nitrogen is a critical component for plant development and is directly linked to flowering frequency and duration.2 Potassium (K) promotes overall leaf health, which can help cotton plants maintain a heavy boll load.4

Time of season. Boll shed increases as the season progresses, especially for cotton crops with a heavy boll load.2 As the end of the season approaches, the roots have taken up nearly all the nutrients they are able to and the plant uses those resources for boll maturity. Boll shed is not typically a concern at this stage.

Q. Can boll shedding be prevented?

Yes and no. As previously mentioned, some level of shedding throughout the season should be expected. Shedding is the plant’s response to stress, which is inevitable even in ideal growing seasons. Controlling every potential stress during the season is impossible, but limiting stress when possible helps preserve boll retention and yield potential.

Understanding potential sources of stress can help when making management decisions for maintaining boll retention and yield potential. Weather conditions are out of your control, but providing adequate nutrition, proper irrigation timing, insect and disease control, and maintaining recommended plant populations can help mitigate seasonal stressors. Keeping notes of when shedding was noticeable can also help growers understand the stressors affecting their crops. Did boll shed occur after cloudy weather? Extreme heat? Was the pivot turned on during pollination?

Q. What are some management tips that can help reduce boll shedding?

- Select plant populations based on the soil type, growing conditions, and overall management of the acres to be planted.

- Focus on establishing a good root system early so the plants can access adequate nutrients and moisture throughout the season.

- If irrigation water is available, use it for crop development and for cooling down the crop during extreme heat.

- Help control rank growth with timely plant growth regulator applications. Protect early set bolls and first-position bolls.

- Scout fields and take control measures to help mitigate damaging insects and/or diseases.

- Apply adequate amounts of nutrients, including micronutrients, by basing fertilizer application rates on soil test results and recommendations from a reliable laboratory or your local extension service.2,3

Sources:

1 Verbree, D. 2013. Cotton fruit-shedding – who’s to blame. The University of Tennessee, UTcrops News Blog. https://news.utcrops.com/2013/08/cotton-fruit-shedding-whos-to-blame/

2 Guinn, G. 1982. Cause of square and boll shedding in cotton. United States Department of Agriculture. Technical Bulletin Number 1672. http://cotton.tamu.edu/General%20Production/Causes%20of%20Square%20and%20Boll%20Shedding%20in%20Cotton-complete.pdf

3 Hake, K., Guinn, G., and Oosterhuis, D. 1989. Environmental causes of shed. National Cotton Council, Physiology Today. https://www.cotton.org/tech/physiology/cpt/plantphysiology/upload/CPT-Dec89-REPOP.pdf

4 Stewart, S. 2012. Fruit loss in cotton and potassium deficiency symptoms. The University of Tennessee, UTcrops News Blog. http://news.utcrops.com/2012/07/fruit-loss-in-cotton-and-potassium-deficency-symptoms/

Web sources verified 07/31/24. 1413_148490

Seed Brands & Traits

Crop Protection

Disclaimer

Always read and follow pesticide label directions, insect resistance management requirements (where applicable), and grain marketing and all other stewardship practices.

©2024 Bayer Group. All rights reserved.